More Than One Way to Work

According to a recent startup survey, 49% of founders are on the verge of quitting. One commented, "I cannot sustain this rhythm anymore. Solving problems seems the only purpose in my life and while doing it my mental and physical health is deteriorating."

This feels relatable. The startup workload is indeed relenting, which raises the question on how to effectively manage it. There are three common prescriptions:

- Hustle culture: "14 hour days? Hell yeah! No-one won gold leaving the office at 5. Let's go!"

- Slow productivity: "Seriously? Work smarter not harder, dumbass."

- Indie hacking: "Why spend your life grinding at the office when you could be making $40K a month, working 4 hours a week from a beach in Bali?"

Each approach has its benefits, but as soon as one approach is perceived as the right way it takes on a certain toxic flavour. That's not a broad swipe at the proponents of different working styles. It's on me to see them as a range of options. But in the age of social media, it's just too easy to read between the lines.

| What they're saying | What I hear | Reality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indie hacker | Do less for more by keeping it small and simple | You should find success more easily | Takes luck, prominence and/or outlier skills (likely forged with hard work) |

| Slow productivity | Focus on one thing at a time, and work within sensible boundaries | You should conform | Works best in stable, predictable contexts |

| Hustle culture | To make a big impact you need to work really really hard | You are not working hard enough | It's only satisfying if you win; if you don't, burnout is likely |

Feeling judged is one thing, but what happens when a work culture actually turns toxic? One founder shared with me recently how he introduced a new employee to one of his investors. Unprompted and off-script, the investor took it upon themselves to brief the new employee on how startup life would mean working late and sacrificing their evenings.

When sacrifices are made continually, without break or reward, we can expect burnout to follow. It's not the long hours, per se, that cause burnout, it's being subjected to unrelenting stressors. Whether that's a firehose of deadlines, endless conflicts with a colleague, or working on a project that never ships, persist at anything for long enough, and eventually you will lose all motivation. (In the most severe cases, even the motivation to move your muscles).

The power of hustle culture unfortunately cuts both ways. Hard work can compound into extraordinary success, but being overworked compounds into physical and mental demise.

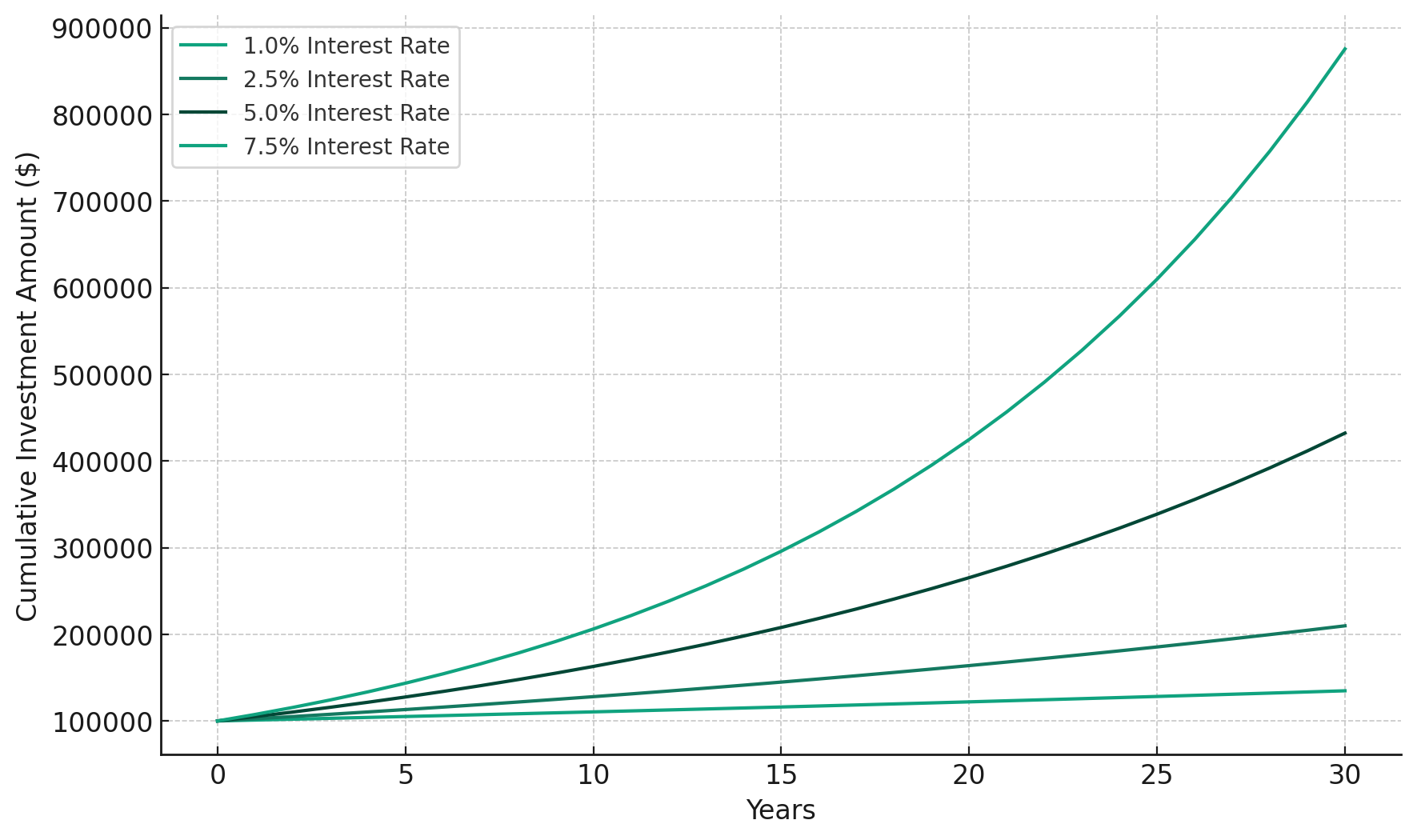

Unfortunately for me, I never had an intuition for compound interest. As a child, I was told it is the most powerful force in the universe – I realise now, by people who built up their savings through the 70s and 80s. In a low interest rate environment – such as the one I spent most of my adult life – the magic of compound interest does not kick in until after death.

That's a useful metaphor perhaps for the widening generational wealth gap – or more poignantly, the gap between the expectations inherited by my generation and the current economic reality.

Accordingly, a work culture rebellion is supposedly sweeping through social media. I say supposedly; I have little more insight on what happens inside TikTok than a boomer with a broadsheet, but if the reporting is to be believed, Gen Z has finally called BS. The social contract is broken, hustle culture leads only to cycles of burnout – bring on the soft life, quiet quitting and bare minimum Mondays.

I broadly agree with the prognosis, and stand in solidarity with those who are demanding that labour gets an upgrade from the industrial revolution. But there's a crinkle: I really like work. And as the cultural tide changes direction, I find myself swimming against the flow.

This is an odd moment to make such a disclosure. Just yesterday, I met with a friend, and – in my own version of a bare minimum Monday – I explained how I could barely muster the motivation to get out of bed, let alone write a line of code. Ostensibly, I am burned out myself.

If that's true, then it is not my first rodeo. In 2021, I was forced to learn the practice of stopping. To stop and to stay stopped until all my energy and motivation had returned. After a short bout of covid, I realised that I had been left with chronic fatigue. Nothing and no-one can predict how long chronic fatigue will last. You hope it will pass quickly, but even this is a dangerous impulse – resisting fatigue only aggravates it.

I learned to accept my fatigue, and after nine months, my energy levels returned to a normal level. My celebrations were short lived. On reflection, I may have booted back up too quickly, as a few weeks later I was in hospital getting an appendicectomy; and no sooner as I recovered from that I was floored again (quite literally) by a vertigo episode that took months to fully recover from.

So now, when I think about how far I am willing to push myself to achieve my goals – even if I don't always follow my own advice – I truly believe that good sleep, diet and exercise are non-negotiable.

As we tuck into lunch, my friend is listening to my struggles intently, before turning to offer her advice. Sahir is only a few days from the start of her cycle trip to Pakistan, so I suspect this will be advice she will soon draw on herself.

Long distance cycling was a good frame to place our discussion. A few years ago I cycled around New Zealand and had the best time of my life. The following year, I raised my game and cycled up the UK, averaging 170 miles a day. At the final pit stop, just 50 miles from John o'Groats, I collapsed on the heath in pain, and began sobbing next to a dead fox.

The body, like the mind, has limits – and on that day I found mine. This was far from the best time of my life. For the following two weeks I was exhausted. On lunch breaks I would take naps on the meeting room sofa. I didn't want to ride a bike again for months. I kept catching colds. Was all that pain really worth it? Just to be able to boast on my blog that I made it into the top ten of Strava's global leaderboard?

Hell. Freakin'. Yeah.

What can I say? Some people just enjoy the pain. Type one fun is delightful in the moment. Type two fun is utterly awful in the moment, but delightful afterwards. At level three, the fun never materialises, but some people like that too.

If you're feeling that I just trojan-horsed hustle porn into my wholesome blog, please don't bolt just yet. I'd very much like to introduce you to the indie hacker community. According to its leaders, you can skip all that pain cosplaying Jensen Huang, and fast-forward straight to revenue.

Don't take my word for it though. Watch for yourself as indie hacking legends #BuildInPublic, turning their weekend projects into recurring cash cows. This leaves just one question: how do you replicate their success? Let me tell you. By subscribing to their newsletter, or pre-ordering their book, or buying their coding boilerplate. See what happened there? Seductive tales of success just doubled up as a distribution channel. Clever.

The reality is that their business model is not replicable. There are replicable indie hacker business models, but they're probably not the ones you are being sold. It didn't take long before one or two people realised that they're at the bottom of the pyramid scheme.

Which brings us full circle, and back to slow productivity, the sensible middle ground. How many folks do you see writing posts complaining that work-life balance is damaging their mental health?

Ahem. If I may say a few words…

For most founders, work-life balance is an unreasonable expectation. Startups are bloody hard work, so let's not make people feel worse by pretending that it should be easy.

And, let's also not reinforce the idea that people who work a lot have an unbalanced life. When we talk about work-life balance, I think what we are often striving to express is a stress-release balance. Stress is useful – it gets us moving - but it must be accompanied by some kind of release valve. For some people that is an evening spent cooking a casserole and drinking red wine, for others it's watching Netflix or playing five-a-side. For me, I want the cycle to resolve within the context of work itself. Fortunately, I am in a position to make that possible.

The truth is that I love elements of slow work – doing one thing at a time, and doing it well – but I suck at traditional work-life balance. My brain is just not wired that way. I build up to a project, and then I dive in. Sometimes I overwork, and from time to time I crash. But that's not the main threat to my mental health. Prolonged mundanity is what gets me. That's perhaps more bummed out than it is burnt out, but either way it can be a tricky spot to get out of.

The startup journey is long, and each founder has to forge their own path. It's a marathon, not a sprint. Unless, of course, you are a sprinter, in which case, it's probably going to be a series of sprints. You do you.

"Do you believe you can achieve your goal?", Sahir finally asks me. (At this point I am absolutely getting a free coaching session). I pause to reflect, but the answer is instinctively yes – and with that realisation comes a shift in my mood. As I project my mind forward, I realise there are in fact many possibilities, each interwoven with failure and success. The range of outcomes excites me. Hope is not lost.

"Well then, if you believe that you will eventually succeed, the struggle you're feeling today will only make success all the sweeter when it finally arrives".

Ah yes, that's right… I actually like this process.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this, subscribe for free to get next month's post delivered direct to your inbox.